Understanding Barrett’s Esophagus

The digestive tract is a robust bodily system that is responsible for converting the food we eat into energy that is usable by cells all over the body. As adaptable as our digestive system is, though, it can still be subject to a wide variety of disorders and diseases that are treated by gastroenterologists. One common problem, known familiarly as heartburn, can become a chronic problem known as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). While GERD is a relatively common concern, it can sometimes lead to another condition called Barrett’s esophagus.

What is Barrett’s Esophagus?

Unlike many other gastrointestinal conditions that are characterized by abnormal function or tissue inflammation, Barrett’s esophagus involves a change in the cells that line the lower esophagus. This abnormal change is known as intestinal metaplasia because the cells themselves actually transform into a different type of cell. Rather than the stratified epithelial cells that normally line the esophagus, in Barrett’s esophagus the cells morph into columnar epithelial cells like those that line the small intestine and large intestine.

In a healthy gastrointestinal tract, columnar and stratified squamous epithelial cells act in different ways and are adapted to the main function of the part of the tract they line. One of the main differences between the two types of cells is that the columnar cells are better at providing protection from stomach acid and other gastric juices that are efficient at breaking down food. The main concern with Barrett’s esophagus, however, is that these transformed cells make it more likely for the person to develop a cancer of the esophagus known as adenocarcinoma.

Types of Barrett’s Esophagus

Any intestinal metaplasia that leads to a replacement of the esophagus’ epithelial cells is known as Barrett’s esophagus, but there are four different categories of cells that can be involved: nondysplastic, low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and frank carcinoma. These categories are based on whether or not dysplasia (abnormal cell growth) is present and are primarily used to determine the severity of the condition as well as the treatment type. The diagnosis requires a biopsy of cells from the esophagus:

- Nondysplastic: This means that, even though the cells may have gone through a transformation, the replaced cells are not pre-malignant and therefore won’t lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Low-Grade Dysplasia: Having low-grade dysplasia means that the cells are certainly abnormal but also still pre-malignant. While there is a higher likelihood of cancer with this type, most people in this category don’t develop cancer.

- High-Grade Dysplasia: When high-grade dysplasia is determined, it means that the cells are even more abnormal and more likely to lead to cancer. People with high-grade dysplasia are at increased risk of esophageal cancer.

- Frank Carcinoma: This designation means that the amount of abnormality is severe and that the presence of cancerous cells is unmistakable.

What Causes Barrett’s Esophagus?

Practitioners of gastroenterology don’t know the exact cause of Barrett’s esophagus, but research suggests that it is an example of the body adapting to chronic acid reflux as seen in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). While GERD isn’t the only possible cause of acid reflux, it does appear to be one of the most common reasons behind the development of metaplasia in Barrett’s esophagus.

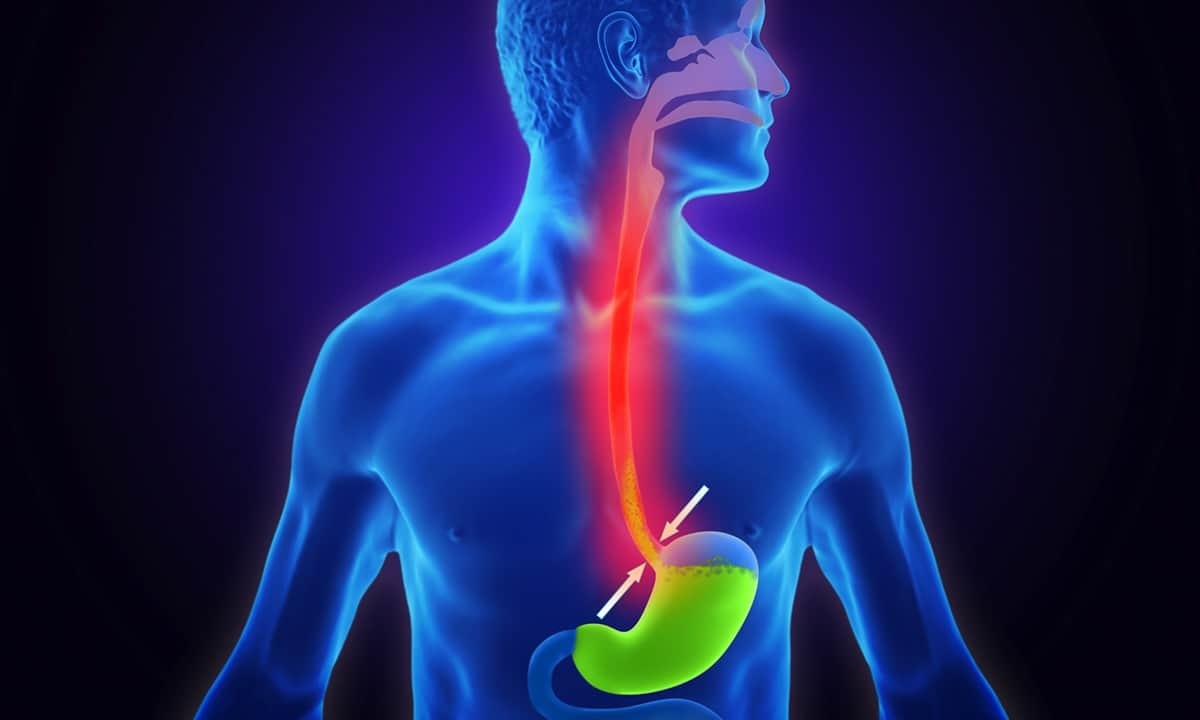

Under normal circumstances, food from the esophagus enters the stomach through the lower esophageal sphincter, a ring of muscle that prevents stomach contents from backing up into the esophagus. In patients with GERD, though, that sphincter is weakened and doesn’t open and close normally. Because of this, stomach acid can slosh up into the esophagus and cause a variety of symptoms like heartburn or chest pain. But because GERD is a chronic condition, the repeated exposure of the esophagus to stomach acid can eventually trigger the adaptation noted above from stratified to columnar epithelial cells.

Symptoms of Barrett’s Esophagus

Surprisingly, Barrett’s esophagus doesn’t have associated symptoms. The intestinal metaplasia does obviously transform the cells lining the esophagus, but that transformation in and of itself doesn’t cause any symptoms. Instead, a person who has developed the condition is more likely to have symptoms that derive from GERD or whatever other underlying condition may have caused the chronic acid reflux. For those who have been diagnosed with GERD (or those who may have it and haven’t been diagnosed yet), the following are some common symptoms to watch out for that may also indicate Barrett’s esophagus:

- heartburn (especially the severe type that may wake you up)

- difficulty swallowing

- sore throat

- a sensation of food being stuck in your esophagus

- bad breath

- sour taste in your mouth

- unexpected weight loss

- blood in stool

- vomiting

- nausea

Diagnosis of Barrett’s Esophagus

The only way to know for sure whether a patient has Barrett’s esophagus is through a biopsy of the lining of the esophagus. In order to get a biopsy, the gastroenterologist must use an upper endoscopy. As with all endoscopic procedures, this imaging test involves inserting a thin tube called an endoscope through the mouth and down the esophagus. In addition to visualizing the tissue, the endoscope also has small tools mounted on the end that can take tissue samples. It is then through the biopsy process that the doctor can determine which category of cells have developed.

How is Barrett’s Esophagus Treated?

The type of treatment for this condition is based primarily on information determined from the biopsy. If no dysplasia is found, that means no precancerous cells were detected. This is great news, though the doctor will undoubtedly want to monitor the condition at regular intervals to ensure that there continues to be no dysplasia. In these circumstances the only treatment necessary would be to manage or mitigate the symptoms associated with GERD or any other cause of chronic reflux.

If the biopsy shows abnormal growth with dysplasia, that will indicate the presence of cells that may be precancerous. As noted above, this might mean a result that is designated as low-grade or high-grade dysplasia. Low-grade dysplasia means that there are some precancerous cells yet not enough to be a true problem. There likely won’t be any treatment necessary, but the doctor will want to monitor the situation over time.

If the biopsy shows high-grade dysplasia, that means there are a substantial number of abnormal cells that bring a higher risk of cancer. Depending on what the doctor sees during the gastrointestinal endoscopy, there are a number of treatment options. Radiofrequency ablation is the most common procedure, and it involves using heat generated from radio waves to burn off affected tissue. The doctor may also use cryotherapy to freeze off tissue or resection to cut away affected tissue. If there is severe dysplasia or actual cancer, surgery known as an esophagectomy may be necessary to remove a larger section of the esophagus.

When to See a Doctor

Since there aren’t any specific symptoms associated with Barrett’s esophagus, there typically aren’t any obvious signs to watch out for. Nevertheless, anyone who has GERD or a history of acid reflux should be wary of worsening symptoms they’ve previously experienced. If you have been having recurring heartburn or any of the other symptoms noted above, it’s best to seek medical advice from a gastroenterologist like the board-certified physicians at Cary Gastro. We are passionate about providing excellent digestive health care. Please contact us to request an appointment.