The Causes and Symptoms of Portal Hypertension

When the liver begins to fail, the effects often ripple through multiple organ systems in ways that aren’t immediately obvious. Portal hypertension is one of the most serious complications of chronic liver disease, often requiring specialized care from a gastroenterologist or hepatologist. While this condition may develop gradually, its long-term impact on health and quality of life can be significant. Advances in diagnosis and treatment have improved outcomes, but early detection and careful management remain essential to avoiding serious complications.

What Is Portal Hypertension?

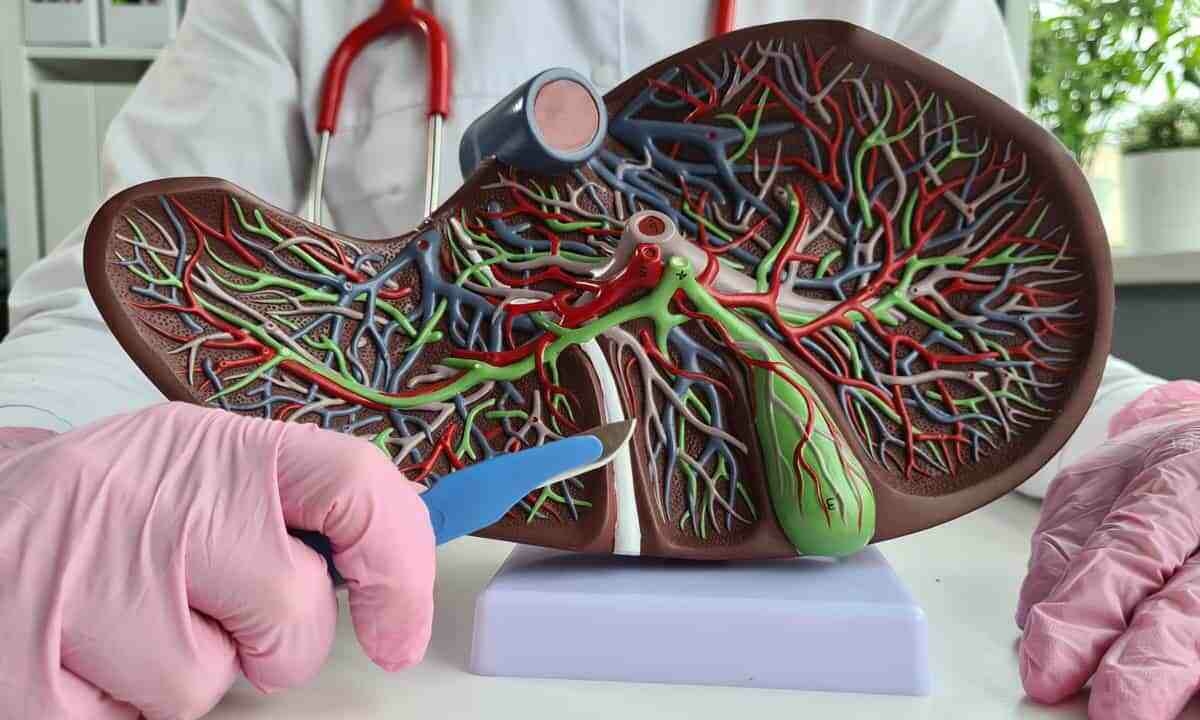

Portal hypertension occurs when blood pressure increases within the portal venous system, the network of blood vessels that carries blood from the digestive organs to the liver. In normal circulation, blood flows from the intestines, spleen, and pancreas through the portal vein and into the liver, where it undergoes filtration before continuing to the heart. When this blood flow meets resistance, typically due to liver damage or blockages, pressure builds within the portal system, creating a condition known as portal hypertension.

The portal vein normally maintains a pressure between 5-10 mmHg. Portal hypertension is typically defined as having a portal pressure above 10 mmHg, but symptoms don’t usually develop until pressure rises above 12 mmHg. As pressure increases, the body attempts to compensate by diverting blood through alternative pathways called collateral vessels. These collateral vessels often include veins in the esophagus, stomach, rectum, and abdominal wall, which aren’t designed to handle this increased blood flow and pressure.

The development of these collateral vessels represents the body’s attempt to bypass the blocked or resistant blood flow through the liver. Unfortunately, these alternative pathways can lead to serious complications. The thin-walled veins in the esophagus and stomach may enlarge and become varicose (called varices), creating a risk for rupture and potentially life-threatening bleeding. Additionally, the increased pressure can force fluid to leak from blood vessels into the abdominal cavity, leading to ascites or other changes in organ systems throughout the body.

Unlike primary hypertension (high blood pressure in the arterial system), which can often remain asymptomatic for years, portal hypertension frequently produces noticeable effects as pressure rises and collateral vessels develop. The severity of these effects depends on multiple factors, including the underlying cause, the degree of pressure elevation, and how quickly the condition progressed.1

What Causes Portal Hypertension?

Since portal hypertension isn’t a disease in itself, its presence typically signals an underlying condition that interferes with normal blood flow through the liver. In most cases, increased pressure results from liver damage that disrupts circulation within the portal venous system. Several conditions can interfere with normal circulation through the liver and raise pressure in the portal venous system. Some of the most common or clinically significant causes include:

- Cirrhosis of the liver: Cirrhosis is the most common cause of portal hypertension in the United States, and it can occur when healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis) due to long-term damage. This scarring distorts the liver’s internal structure, creating resistance to blood flow. Common causes of cirrhosis include alcohol-related liver disease, viral hepatitis B and C, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and autoimmune liver diseases.

- Portal vein thrombosis: Formation of blood clots within the portal vein can block blood flow, leading to increased pressure in the vessels behind the blockage. This condition may develop from blood clotting disorders, abdominal inflammation, abdominal infections, or cancer. Portal vein thrombosis sometimes occurs in otherwise healthy livers, particularly in patients with inherited or acquired hypercoagulable states.

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: This rare condition involves blockage of the hepatic veins that carry blood from the liver to the heart. The obstruction can result from blood clots, tumors, or structural abnormalities, causing blood to back up in the liver and increasing portal pressure. Patients with blood disorders that increase clotting risk have higher chances of developing this syndrome.

- Schistosomiasis: A parasitic infection common in parts of Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and Asia. The parasites’ eggs lodge in small portal blood vessels, causing inflammation and fibrosis that can lead to severe portal hypertension. Schistosomiasis is one of the most common causes of portal hypertension worldwide, though it remains relatively rare in the United States.

- Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: This condition is characterized by widespread transformation of normal liver tissue into small regenerative nodules. The process can compress the small veins within the liver, causing portal hypertension without significant fibrosis. It often occurs in patients with systemic diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or after certain medications.

- Congenital hepatic fibrosis: In this rare condition, bile ducts and blood vessels in the liver develop abnormally and can lead to portal hypertension even in the absence of cirrhosis. It often manifests in childhood or early adulthood and may be associated with kidney abnormalities.2

Signs and Symptoms of Portal Hypertension

Portal hypertension often progresses slowly, and early signs may be minimal or go unnoticed. As pressure builds in the portal venous system, however, it can give rise to a range of complications, some of which may develop suddenly or become life-threatening if left untreated. These effects typically reflect the body’s attempt to adapt to increased resistance in blood flow and can vary widely from person to person. Below are some of the more common signs and complications associated with portal hypertension:

- Ascites: One of the most common signs of portal hypertension is ascites, the term for a fluid buildup in the abdominal cavity. This occurs when increased pressure forces fluid out of blood vessels and into the peritoneal space, leading to abdominal swelling, weight gain, and increased girth. Severe cases can cause discomfort, shortness of breath, reduced appetite, and increased risk of infection. Its presence often signals advanced liver disease.

- Esophageal and gastric varices: These enlarged, fragile veins form when blood reroutes through smaller vessels due to resistance in the portal vein. Although varices themselves don’t cause symptoms, they can rupture and bleed, leading to vomiting blood, black or bloody stools, and potentially life-threatening hemorrhage. Around 50% of patients with cirrhosis develop varices, and one-third of those experience bleeding episodes.

- Enlarged spleen: An enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) often results from blood backing up into the splenic vein. This can lead to lower platelet and white blood cell counts, as well as a feeling of fullness or discomfort in the upper left abdomen.

- Hepatic encephalopathy: When reduced liver function impairs the body’s ability to filter toxins from the blood, it can begin to affect brain function. This condition, known as hepatic encephalopathy, can cause a range of neurological symptoms such as mild confusion, memory issues, and sleep changes, as well as more serious signs like disorientation, drowsiness, or even coma.

- Portal hypertensive gastropathy: Increased pressure in the stomach’s blood vessels can lead to changes in the stomach lining that result in slow, chronic bleeding. While this rarely causes visible bleeding, it may lead to iron deficiency anemia and fatigue over time. The condition is often identified during endoscopy by a distinct mosaic-like pattern in the stomach lining.

- Hepatorenal syndrome: In some patients, advanced portal hypertension affects kidney function, leading to progressive failure without direct kidney damage. It typically occurs in those with cirrhosis and ascites, and symptoms may include reduced urination, fluid retention, and electrolyte imbalances.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Because portal hypertension results from deeper changes in liver function and blood flow, diagnosis typically involves multiple tools. Blood tests help assess overall liver function, while imaging studies like ultrasound or CT can detect changes in the portal system or surrounding organs. Endoscopy is often used to identify visible signs that suggest elevated portal pressure like esophageal or gastric varices. In some cases, a more specialized test may measure the pressure gradient between the portal and hepatic veins to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment.

Management focuses on lowering portal pressure, preventing complications, and addressing the underlying cause. Nonselective beta-blockers may be prescribed to reduce bleeding risk, while diuretics can help relieve fluid buildup from ascites. Endoscopic procedures such as band ligation treat varices directly. In more advanced cases, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be used to divert blood flow and reduce strain on the liver. For patients with end-stage liver disease, liver transplantation may offer the most comprehensive solution.

Cary Gastro Can Help

Portal hypertension is a serious condition that requires careful medical evaluation and ongoing management. If you’re experiencing symptoms related to liver disease or complications from portal hypertension, consulting with a gastroenterologist is an important step toward effective care. The team at Cary Gastro provides comprehensive services for patients with liver and digestive health concerns. Contact us today to schedule an appointment and take the next step toward better digestive health.

1https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507718/

2https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3971388/