Polypectomy: How Polyps are Removed

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, incidence of colorectal cancer have been dropping steadily since the 1980s, and this decline can be attributed to more people getting screened and an overall greater emphasis on healthy lifestyle habits. At the same time, unfortunately, rates have been increasing for people under age 50. This is why regular cancer screenings are important for everyone over the age of 45 or for people over 40 who have a family history of colon cancer. When gastroenterologists perform these screenings, they’re primarily looking for one of the earliest signs of the potential for cancer: polyps.

What are Colon Polyps?

Colon polyps are small, abnormal growths that can develop in the lining of the large intestine or rectum. While they are typically benign initially, they can continue to grow and eventually become cancerous. Whether or not cancer is more likely is somewhat related to size; only 1% of small polyps (less than 1 cm) turn out to be cancer, but the risk increases for larger polyps. We are also overall more likely to develop polyps as we get older. Additionally, for reasons that aren’t fully understood, men are marginally more likely to develop polyps.

There are many different kinds of polyps, and they can be classified by size, location, likelihood of malignancy, or structure. For example, there are two basic forms polyps can take: sessile or pedunculated; sessile polyps lie flat against the colon while pedunculated polyps grow on the end of a stalk like a mushroom. Generally speaking, though, there are five main categories that most doctors use when evaluating a polyp:

- Adenomatous: Adenomatous polyps (or simply adenomas) make up about 70% of all polyps, and that makes them the most common type. Even though only a small fraction of adenomas will become cancerous, the fact remains that nearly all polyps that do become cancerous start out as adenomatous polyps. This type can be further classified into subtypes: tubular, villous, or tubulovillous. Tubular adenomas are the most common subtype, but they rarely become malignant. Tubulovillous adenomas are the next most likely to be malignant, and villous adenomas have the highest risk of becoming malignant.

- Hyperplastic: Hyperplastic polyps are typically benign and have a low chance of becoming cancerous, but the standard practice is to perform a polyp removal procedure when they’re detected out of an abundance of caution.

- Serrated: Serrated polyps are so named because of the sawtooth pattern that can be seen when viewed under a microscope. Serrated polyps in general are less common and tend to be sessile (flat), but they can also be found in an adenomatous form that has a slightly elevated cancer risk.

- Inflammatory: An inflammatory polyp is almost always associated with gastrointestinal conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, and thus they aren’t commonly found outside of an underlying inflammatory condition.

- Juvenile: Juvenile polyps are noncancerous growths primarily found in the colons of children, but they can happen to a person of any age. These rare abnormal growths are hardly ever symptomatic, but they can sometimes cause intestinal bleeding.

It's worth reiterating that not all or even most colon polyps will develop into colorectal cancer. But since the vast majority of colon cancer cases begin as a polyp, it’s important to get regular screenings when you get to the appropriate age. This is especially crucial with colon cancer since it can take many years for a polyp to become a cancerous tumor. Moreover, symptoms of colon cancer rarely present until later stages; this means that by the time you notice symptoms, it will likely already be at an advanced (and dangerous) stage.

What is Involved in a Colon Polypectomy Procedure?

Many people live for years with one or more polyps in their colon without being aware of it, but in some rare circumstances the presence of a polyp can lead to symptoms like abdominal pain, bloating, and cramping. For the most part, though, polyps are only detected inadvertently when going through a routine imaging test like a colonoscopy or endoscopy. When they are found, and depending on where they are and how they’re structured, there are several main methods for the removal of a polyp via polypectomy:

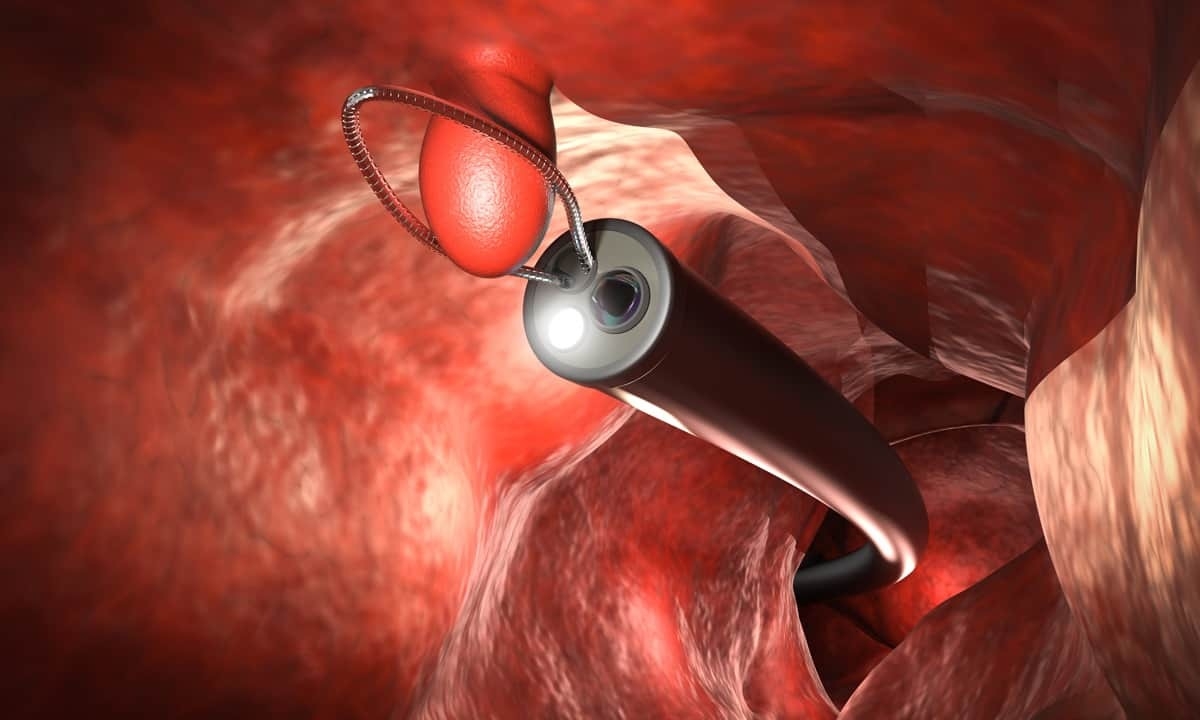

- Colonoscopy: A colonoscope is made of a long, flexible tube with several surgical tools and a small camera mounted on the end. After being inserted through the rectum, the doctor can directly visualize the walls of the colon and look for abnormalities. If a polyp is found, it can be simply cut out with biopsy forceps. In other circumstances, a hot snare polypectomy can be used; this method involves looping a small wire around the polyp that cuts through the base. And because the wire is heated with an electric current, the tiny cut is immediately cauterized.

- EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection is a more advanced technique used to remove larger or flat polyps. It involves injecting a solution beneath the polyp to lift it away from the colon wall so that a snare or forceps can remove it. For tumors, lesions, or larger masses of polyp tissue that reach deeper into the wall of the colon, another process called endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is usually more effective.

- Surgery: In some cases when the polyps are too large or unwieldy, surgical removal of a portion of the colon (colectomy) may be necessary. This is more commonly done if cancer is already present or if there are other complications.

Possible Postpolypectomy Complications

A polypectomy can be an important preventive measure for reducing the risk of colorectal cancer, and it is generally a safe and well-tolerated procedure when performed by experienced healthcare professionals. The choice of method depends on factors such as the size, type, and location of the polyps, as well as the patient's overall health and medical history. Like any medical procedure, however, a polypectomy has some risks and potential complications. While relatively rare, these risks should be taken into consideration:

- Bleeding: Bleeding is the most common complication of polypectomy even though the cuts used in the procedure are very small. Most cases of bleeding are minor, but it’s possible for severe bleeding to require additional interventions or surgery.

- Perforation: In very rare cases, a polypectomy can lead to a perforation in the wall of the colon. This can allow the escape of gas and bacteria from the colon to leach into the abdominal cavity and potentially cause an infection.

- Infection: Apart from the circumstances of a perforation noted above, a polypectomy can also lead to infection if bacteria from the colon traveled to another area of the body or if bacteria on the surgical tools was accidentally introduced to the colon.

- Residual polyps: Sometimes not all polyps may be completely removed during the initial procedure. Residual polyps or those that were missed can continue to grow and may require additional procedures for removal.

- Sedation problems: Adverse reactions to sedation are rare, but they can include allergies, breathing difficulties, or changes in heart rate and blood pressure.

- Pain: Patients may experience abdominal discomfort or pain following the procedure, though it tends to be mild and temporary.

Get Screened Today at Cary Gastroenterology

It’s undoubtedly great news that the incidence of colorectal cancer has been decreasing for people over the age of 50, but that has only happened because more people are getting screened. At Cary Gastro, we are dedicated to helping this trend continue by offering regular cancer screenings. If you’re over 45 or you have a history of colon cancer in your family, it may be time to get checked out. Colorectal cancer takes years to develop, and it’s always better to catch it as early as possible. Please contact us today to request an appointment.